Generated with AI:

Model telling using edge-detection (not sure it did, but still), followed by another generation:

With no intermediary prompt.

How computer vision algorithms “see” the world:

Generated with AI:

Model telling using edge-detection (not sure it did, but still), followed by another generation:

With no intermediary prompt.

How computer vision algorithms “see” the world:

Noun.

1.a.

1593–

The action or process of inferring; the drawing of a conclusion from known or assumed facts or statements; esp. in Logic, the forming of a conclusion from data or premisses, either by inductive or deductive methods; reasoning from something known or assumed to something else which follows from it; = illation n. Also (with plural), a particular act of inferring; the logical form in which this is expressed.

Additional sense (2024)

1960–

Originally: a simulated process of drawing a conclusion performed by a computer, program, etc. In later use: spec. the process by which a trained artificial intelligence program, system, etc., makes predictions, generates output, or otherwise responds to new inputs.

Oxford English Dictionary, “inference (n.), additional sense,” June 2025, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/7585762308.

Whether language is necessary for intelligence remains a longstanding question in the philosophy of language. Every field of research—from neuroscience to psychology, linguistics, and computer science—has its own perspective on this issue.

One important point to consider: Language isn’t always used in problem solving: finding your directions, solving a math problem or a puzzle, adapting your body response to an immediate threat… all actions exhibiting a form of intelligence.

From a linguistic perspective, does language equal thought? Yes and no. It depends. Read the literature, form your own opinion, and avoid relying on catchphrases or leaderboard scores. Benchmarks are inherently relative, and the field is far from unanimous on how to define intelligence or intelligent behavior.

There are always nuances in how we perceive “reality.”

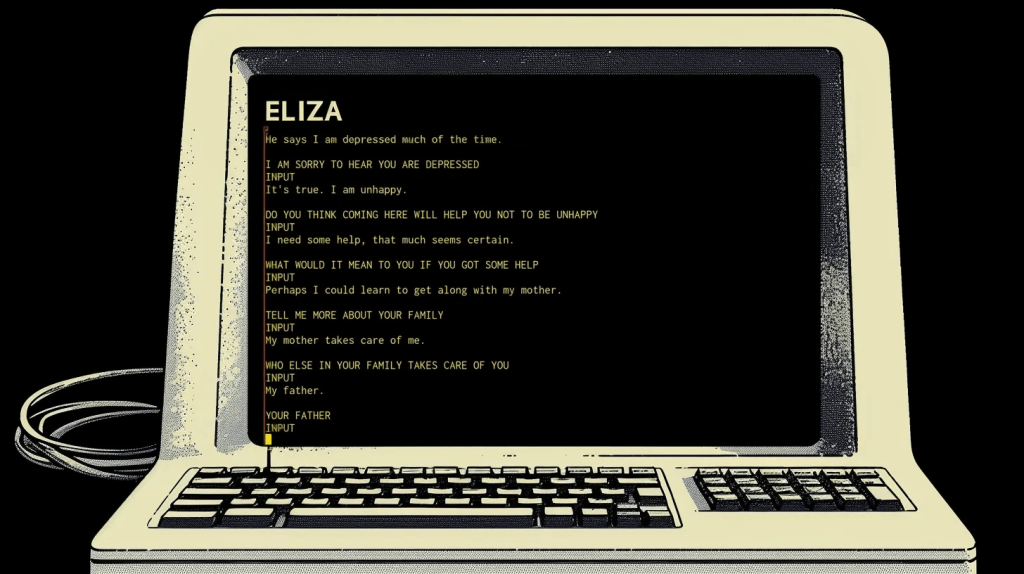

Image: read about the “Eliza effect”

A few words on fake news and online deception countermeasures.

We consume information all the time. Social media platforms like X (ex-Twitter) have become essential channels for information dissemination. However, they also pose significant challenges in terms of verifying the authenticity of the content shared. Deception in social media can take many forms, from fake news to manipulated profiles, and it’s crucial for users to develop the skills necessary to identify and critically evaluate the information they encounter.

Deception on social media often involves linguistic and cognitive strategies designed to manipulate or mislead users. One of the most common tactics is the use of emotional appeals. Deceptive content frequently employs emotional language to persuade readers, appealing to emotions such as fear, anger, or even sympathy.

An example of emotional appeal in a tweet: “WE WILL RIOT! Michelle Obama’s Mom Will Receive $160k Every Year Out Of Taxpayers’ Pockets!”

Here critical thinking involves recognizing these tactics and evaluating the underlying evidence. For example, if a tweet uses overly emotive language to make a claim, it’s important to look beyond the emotional appeal and seek concrete evidence which support the assertion. Additionally, truthful messages tend to be more specific and detailed, while deceptive ones often lack concrete facts or evidence to support their claims. Be careful with vague statements or promises that seem too good (or bad) to be true, as these can be indicative of deception.

Deceptive content might also include more words related to thinking or believing, which can be attempts to justify false information. Overuse of cognitive words like “think,” “believe,” or “consider” can be indicative of deception. Furthermore, deceptive messages often contain more negative statements or complaints, which can be used to deflect suspicion or create a false narrative. Inconsistencies in the narrative are another red flag; deceptive content may exhibit contradictions or changes in the story over time. By being aware of these linguistic features, users can better identify potentially deceptive content and approach it with a critical mindset.

“I think this news story is true, and it’s shocking what they’re hiding from us.”

“Some experts believe …”

Critical thinking is essential when we engage with content on the internet. One of the most important strategies is evidence-based evaluation. Always seek evidence to support claims, rather than relying solely on emotional appeals or personal beliefs. Critical thinking involves evaluating information based on facts, which helps to distinguish between credible and deceptive content. Additionally, analyzing the structure and soundness of arguments presented in the content is crucial. Look for logical fallacies or biases that might undermine the credibility of the message.

One logical fallacy could be attacking the person making the argument, instead of the argument itself, or presenting only two options as if they are the only possibilities when, in fact, there are more.

Understanding the context in which information is presented can also help assess its credibility and potential biases. Consider the author’s background, the topic’s relevance, and any potential conflicts of interest.

Deception involves complex cognitive processes, including cognitive load, executive functions, and emotional regulation. Lying requires more cognitive effort than telling the truth, which can lead to linguistic cues such as inconsistencies or overuse of certain phrases. In social media, this might manifest as more cautious language or structured arguments. Executive functions like planning, decision-making, and inhibiting the truth are also involved in deception. These processes can result in more structured arguments in written texts, though they might also lead to errors or inconsistencies if not managed effectively. Emotional regulation is another critical aspect; liars often need to manage their emotions to appear convincing. In social media, this might be evident through the use of emotional language or attempts to elicit emotions from the reader. By understanding these cognitive processes, users can better recognize the signs of deception and approach information with a more discerning eye.

Detecting deception in social media requires a combination of linguistic awareness and critical thinking skills. By recognizing the features of deceptive content and employing critical thinking strategies, users can make more informed decisions about the information they consume. Today misinformation can spread rapidly, cultivating these skills is not just beneficial but essential for maintaining a healthy and trustworthy online environment.

Critical thinking as digital literacy: Smith, J., et al.2020.The Use of Critical Thinking to Identify Fake News. Journal of Critical Thinking Studies.

Sharing communities bring together organizations that collaborate to share threat intelligence using the MISP platform. Let’s explore what these communities are and see some of the unique aspects of the MISP Project sharing model.

Each sharing community is formed by entities who share the same goals and values. Sector-specific communities bring together groups of organizations from the same industry to share threat intelligence relevant to their particular sector (Financial sector for ex.). Some other communities involve government agencies, police forces, and other public organizations that collaborate to share threat intelligence (Military, NATO, CERTs). Others can involve closed groups of private organizations that share sensitive threat data among themselves. Sharing communities can have a long-term lifespan, with continuous evolution among their members, or be created for a short period to address specific needs. Sometimes some topical communities, such as the COVID-19 MISP, are established to tackle specific issues.

Benefits of sharing

Participating in MISP communities offers several significant advantages to organizations. One of the primary benefits is an improved threat detection. Access to shared indicators of compromise enhances an organization’s ability to detect and respond to threats more effectively. Mutualized information and correlation engines ensure that organizations have access to IoCs relevant to their needs. This way, MISP communities foster collaboration, enabling organizations to benefit from collective knowledge. This collaborative environment also leads to increased efficiency in analysis, as structured information is shared and used to combat information overload and streamline threat intelligence processing. We’ll see the importance of structured information and standards in future posts. Stay tuned!

Sharing groups

Now that we’ve explored the concept of sharing communities and the sharing model within the MISP Project, let’s look at how it works in practice. MISP provides flexible sharing options to ensure secure and controlled distribution of threat intelligence. Sharing groups allow users to create reusable distribution lists for events and attributes, enabling selective sharing with internal instances and external organizations. The distribution lists and filtered sharing offer distinct options for controlling the flow of sensitive information, ensuring that only authorized parties receive threat data.

There’s a distinction between Sharing Groups and Sharing Communities within MISP. Sharing Groups refer to mechanisms for distributing information within MISP, providing precise control over which data is shared with whom. They are used to define specific distribution rules for events and attributes.

In contrast, Sharing Communities represent groups of users sharing information, focusing on the broader ecosystem of organizations collaborating in threat intelligence.

Several notable MISP communities exist. Two examples are the CIRCL Private Sector Information Sharing Community (MISPPRIV), which brings together international organizations primarily targeting private companies, financial institutions, and IT security firms. In contrast, the FIRST Community focuses specifically on incident response teams, offering both technical and non-technical content.

Takeaway

In summary, MISP communities are vital components of the threat intelligence ecosystem. They share a common set of goals and values. Organizations have multiple options to control the distribution of threat intelligence due to the customization capabilities of the platform and its information-sharing model. Sharing communities enable efficient and effective information sharing processes that supports detection, response, research, and collective action.

MISP Project: https://www.misp-project.org

A few pointers for you to become familiar with the concept of psychological attacks using Internet technologies.

Narrative attacks are strategic efforts to manipulate public perception by spreading false or misleading information about individuals, organizations, or ideas. These attacks aim to create a negative narrative that can significantly influence opinions and behaviors.

By exploiting existing biases and emotions, perpetrators craft narratives that resonate with specific audiences, making them more susceptible to the intended message. These attacks often utilize social media platforms, news outlets, and other communication channels to amplify their reach.

Coordinated campaigns may involve the use of bots, fake accounts, and influencers to ensure that the narrative gains traction quickly. The rapid spread of information in the digital age makes it challenging to counteract these narratives effectively, as they can go viral before accurate information has a chance to surface.

Narrative attacks can be categorized into three main types: misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation. Misinformation refers to the unintentional sharing of false information, while disinformation involves the deliberate spread of lies with the intent to deceive.

Malinformation, on the other hand, involves factual information that is presented out of context to cause harm. Each type poses unique challenges for individuals and organizations trying to navigate the complex landscape of information.

Severe consequences on societies:

Narrative attacks have profound implications for international politics, societal dynamics, and the landscape of cyber warfare. They serve as tools for influencing public opinion and can destabilize political systems, particularly in democratic societies where information plays a crucial role in shaping electoral outcomes and policy decisions.

From a societal perspective, narrative attacks can exacerbate polarization and deepen societal divides. The spread of misinformation can lead to heightened tensions among different groups, creating an environment where extremist views gain traction.

An impact on businesses:

The impact of narrative attacks can be devastating for businesses and institutions. Reputational damage can lead to loss of trust, decreased sales, and even legal repercussions. In some cases, organizations may face significant financial losses.

Countering disinformation:

“Countering disinformation for the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms” https://www.un.org/en/countering-disinformation

A report covering the concepts and narrative attacks and disinformation:

“A Conceptual Analysis of the Overlaps and Differences between Hate Speech, Misinformation and Disinformation” https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/new-report-finds-understanding-differences-harmful-information-is-critical-to-combatting-it

Case: The Doppelganger operations

Copyright Pauline Bourmeau 2026, All Rights Reserved